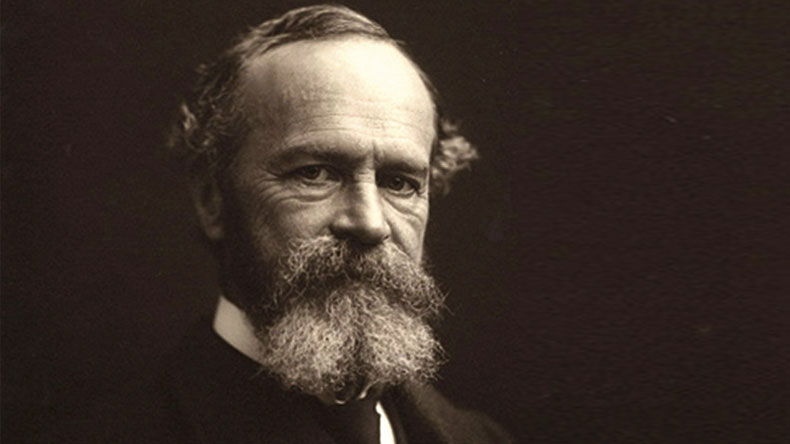

Thoughts about Williams James and How his Mission Aligns with Ours

William James is frequently praised as not only the first, but also the greatest of American Psychologists. It was James who taught the first psychology course on United States soil, created the first psychological laboratory, graduated the first PhD student, and catalyzed excitement about the newly independent discipline with his revolutionary book, Principles of Psychology, published in 1890. Although trained in physiology and medicine, and committed to an empirically grounded psychological science, James nevertheless creatively conceptualized psychological experience with metaphors from the worlds of art, everyday existence, and evolutionary theory. Aware of and holding in high esteem the results of much scientific activity of his time, he was simultaneously a virtuoso of introspective self-observation at the most subtle levels, and wrote eloquently as well as persuasively of what he found. Experience itself-the taking in of the world of objects and its relations, as well as the processes of consciousness surrounding all this-was for James the great fundamental unit of empirical interest in psychology, of reality itself. He resisted with passion and penetrating argument any narrowing of the ways in which such experience might be investigated or understood.

James believed that an adequate American psychology ought to embrace the full range of human psychological phenomena. Nothing was to be excluded; observable behavior, belief and will, the emotions, states of religious transcendence, as well as the interactions of interest, selection, and attention were to him all appropriate and honorable areas of study. The early quest to scientifically catalogue the elementary elements of consciousness-thought by many psychologists of James's day to be discreet, independent, circumscribed simple sensations-was in his estimation an egregious mistake of direction and emphasis that missed the irreducible empirical fact that experience "as such" is never characterized piecemeal or by associations of atomistic sensations. It is instead, he argued, an unbroken, fundamentally indivisible and dynamic flow or "stream of consciousness" that is necessarily personal and holistically given.

“Experience itself-the taking in of the world of objects and its relations, as well as the processes of consciousness surrounding all this-was for James the great fundamental unit of empirical interest in psychology, of reality itself. He resisted with passion and penetrating argument any narrowing of the ways in which such experience might be investigated or understood.”

That James would become recognized world-wide as a genius of the first order, that he would be heralded as the undisputed academic leader of both American Psychology and Philosophy (with no formal training in either), could scarcely have been predicted from the non-systematic and peripatetic education of his childhood and youth. Raised in an unusually child-centered, intellectually permissive, and economically resourceful family, one that had the means to spend years touring the capitals and museums of Europe, James missed the classical, highly structured and prescriptive education of most young people of his class. Instead, he was exposed by his parents to inspirational figures (Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Cullen Bryant, and Bronson Alcott were close family friends) and allowed to follow the dictates of his own curiosity. James developed as a result a seemingly insatiable appetite for the teeming intellectual and artistic world around him. In a manner highly unusual for his time, James was encouraged to freely attend to and feed all his varied interests, which as a youth ranged incorrigibly and vagrantly from fine art and literature and languages, to science and metaphysics and philosophy. Later, as an adolescent and young adult, his wealthy parents would likewise urge him to avoid any career path that might prematurely compromise his intellectual freedom and reach, advising instead that he experiment and explore.

As might be expected from such an unconventional upbringing, the process of bringing coherence and direction to adult life would be a journey of considerable struggle for James, but one that would also ultimately bring wisdom and shape to his mature psychological vision. In the midst of anguish about how to direct himself and his considerable talents, during long periods of acutely poor physical and emotional health, James's varied forays into the adult world included the disappointments of a failed military enlistment, an aborted apprenticeship to the painter William Morris Hunt, a misery-filled trip to the Amazon with the naturalist Louis Agassiz, and the demoralizing realization that having trained in medicine and physiology he had no sustainable interest in medical practice or laboratory work. Later, crediting the healing solace of his marriage to Cambridge school teacher Alice Gibbons, as well as a dramatic rejection of a philosophical determinism that, for him, made meaningless the effort to act responsibly or morally in the world, James found the necessary stability to begin formulating his vision of an American psychology, one unrestricted in scope, guided by evidence gleaned from experience rather than speculation, and methodologically pluralistic. Above all, such a psychology would be, in James's view, devoted to the practical needs of families, workers, and all who might be in emotional distress.

Although at times frustrating his colleagues, and accused of naiveté or self-contradiction, James nonetheless understood any conceptual ordering device, any map of the landscape of our minds or being, to be necessarily incomplete in describing and accounting for what can be known. For him another perspective, another point of view, was always possible; nothing was or could be finished, nothing fully accounted for. Such openness to points of view other than his own led James to advise study rather than summary dismissal and dismantling of the "mind-cure" psychotherapy of late 19th Century New England. It led him to fight for the admission of the brilliant Mary Whiten Calkins to Harvard during a time when women were strictly forbidden, and to refuse to cancel her first seminar when all the male students walked out. To the dismay of his shocked scientific colleagues, James's openness of mind also led him to embrace metaphysical inquiry and the study of religious conversion, and to participate in psychical research about communication with the spirit world. That James valued a divergence of perspectives was evident not only in his teaching and writing, but also in the relationships he formed with a diverse range of students that included Theodore Roosevelt, W.E.B. Dubois, Gertrude Stein, and C.I. Lewis.

“His openness to points of view other than his own...led him to fight for the admission of the brilliant Mary Whiten Calkins to Harvard during a time when women were strictly forbidden, and to refuse to cancel her first seminar when all the male students walked out...”

William James died in August of 1910, in his 67th year, too soon to witness the cataclysmic changes that would soon come to American psychology with the rise of Freudian psychoanalysis and Watsonian behaviorism. During the decades following his death, much of James's central message lay dormant, swept aside by a superabundance of interest in a purely objective psychological science focused solely on observable, measurable, and verifiable phenomena. His emphasis on individual freedom and the experiencing self, set out in sharp contrast to the mechanism and determinism of his day, would not reawaken until mid-20th Century humanistic psychologists lay claim to his ideas and to James as their prophet. His holistic theories of how our minds engage the world and his focus on process and relationship as irreducible features of experienced reality would surface again in the Gestalt psychology that arrived on American shores in the years before World War II, as well as in later movements in ecology and systems theory. Likewise, James's observations about the multiple ways in which we experience our "selves" would be reflected in contemporary theories that challenge the notion of a monolithic and unbroken personal identity. Even his wariness of closed systems of thought, and his belief in the context-dependent, ever-unfinished nature of what can be known would be echoed in the deconstructionist and post-modern critiques of the 21st Century. There is little in our field that cannot in some way be traced back to James's fertile mind.

The core values for which James stood-the importance of the individual, the necessity of experience as a guide to meaningful knowledge, consideration of marginalized perspectives, and action rather than mere discourse in response to injustice-all appear to me well represented at William James College’s. In our efforts to make our intellectual environment home to a plurality of theoretical frameworks and means of research we honor James's call for diversity in scholarly thought and inquiry. In our emphasis on experiential learning and community involvement we clearly align with James's counsel that we always engage the world, rather than intellectual fancy or the authority of others, as our fundamental resource for learning and our best hope to contribute meaningfully in a troubled world. And in our increasing determination to bring to our campus students and faculty from all walks of life and corners of the world, to form a complex community of study and inquiry, it appears to me that we are in considerable harmony with James's most fundamental belief that it is through immersion into the diversity of life that truth is to be encountered, and useful knowledge generated. To the degree that we realize and fully embody his intellectual and service-oriented paradigm, his vision of a psychology that makes a real-world difference, it will be both fitting and proper that we bear the name of William James.

- Tags:

- Around Campus

Topics/Tags

Follow William James College

Media Contact

- Katie O'Hare

- Senior Director of Marketing

- katie_ohare@williamjames.edu

- 617-564-9389